I’ve been asking the questions of musicians over the course of my quarter-century career as a music journalist. But the question I’ve regularly been asked by musicians on the other end of the phone — as well as by fans, industry people, and music geeks — has been, “Are you by any chance related to Jerry Ragovoy?”

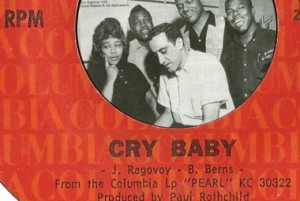

The songwriter Jerry Ragovoy — who died last month at 80 — was never as well known as contemporaries Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Burt Bacharach, Gerry Goffin, and Doc Pomus. This was partly his own fault; early in his career he wrote songs under assumed names, including Norman Meade. (Growing up with a name like Rogovoy, I understand why.) Among real music-heads, however, Ragovoy ruled.

Ragovoy wrote two of the iconic soul ballads of the rock era—“Time Is on My Side,” which was made famous by the Rolling Stones, and “A Piece of My Heart,” which is forever identified with and often wrongly credited to Janis Joplin—but his greatest accomplishments lay outside the pop arena. For unlike his Brill Building contemporaries, most of whom churned out catchy, palatable versions of R&B music that were safe for the pop charts, i.e., intended for white listeners, Ragovoy – who died last week at the age of 80 due to complications from a stroke — for the most part was a hardcore soul man, working with black artists and writing, producing, and arranging hits for the R&B charts by artists who rarely crossed over to pop – people like Garnet Mimms, Howard Tate, Erma Franklin (Aretha’s older sister), and Carl Hall.

Jerry’s father, Nandor Ragovoy, and my grandfather, Joseph Rogovoy, were brothers, which made me Jerry’s first cousin once removed. Jerry, named Jordan at birth, and my father, Lawrence Rogovoy, were born within six months of each other. I didn’t know Jerry well – our families were not close, partly because his family grew up in Philadelphia while the rest of the Rogovoy clan was in New York. Jerry also was not particularly interested in maintaining relationships with his extended family; he explained to me in one of a few phone conversations we had in the last 20 years that he had a strained relationship with his father, who apparently (like my grandfather) was a difficult man, and breaking away from his family was top on his agenda as a teenager, and in no small part propelled him into his career as a music man.

But I didn’t need to know Jerry well to understand him – at least some aspect of him. In photos from the 1960s, he bears a remarkable resemblance to my father (my then-wife audibly gasped when she first saw a photo of Jerry, saying, “That’s your father,” so striking was the similarity in the bearing, the bone structure – even the style of clothes they wore). His father was an optometrist; my grandfather was by training a naturopath (although by profession he owned a dry cleaning business). If Nandor was anything like my grandfather, he was probably also a bigot – not unusual for men of their generation and background – and that could go far to explain why and how Jerry wound up, if you’ll pardon the expression, going native when he went into music.

While his mother, Evelyn, apparently had a beautiful voice and, according to her son, could have been a professional opera singer, Jerry didn’t know that he came from an extended musical family. His grandfather, Herman Rogovoy, was a cantor in Eastern Europe who settled in the Bronx, where he enjoyed a large following and a reputation not only within his synagogue but as a traveling concert performer. Jerry’s uncle Joseph (my grandfather) was a facile pianist who could bang out Rachmaninoff from memory. Like Joe, Jerry was raised on the classics and taught himself to play the piano by studying the works of Ravel, Debussy, Puccini and Stravinsky.

As Jerry explained it, his first exposure to black music came when he got a job as a teenager in an appliance store in a black neighborhood. The store included a record department, which Jerry managed, and he played the latest R&B hits all the time. “That’s what I listened to all day long for four years,” he once told his friend, the rock legend Al Kooper. “And little by little, by osmosis, I absorbed the black musical idiom. I could well have been born black because, ultimately, it became a natural musical expression for me.”

These things sometimes apparently skip generations – my dad, perhaps due to severe hearing loss as a child, is somewhat tone deaf, became a CPA, and has no appreciation for music made after 1955. But as a young teenager I got stung by rock ‘n’ roll – Bob Dylan in particular – and I’ve been a semi-pro singer/guitarist on and off for years and a music critic for most of my adult life. It always seemed to me that somehow I was born to the wrong cousin.

(As for the disparity in the spelling of the last names, that’s simply a case of an immigration officer taking liberties upon arrival. Nandor and Joseph arrived in the U.S. separately; I believe Nandor arrived at the port of New Orleans instead of at New York with his father and brother, whose name, which they pronounced with a soft ‘o,’ got transliterated from the Russian as ‘Rogovoy.’ Nandor’s case officer heard ‘Ragovoy’ and there it was. In the biz, Jerry became known affectionately as “Rags,” and he even named his own record label after his nickname. My father adopted the correct Russian pronunciation of our name, which is Rogovoy with a long ‘o’ in the first syllable.)

While Jerry and Larry were never close, they did attend each other’s bar mitzvahs. When it was clear to my father that I was obsessed with rock music, he remembered he had a cousin who was “in the music business” (although he knew nothing of the nature of his cousin’s work and accomplishments), and the three of us had lunch in New York, where Jerry was based, in 1975.

We met at Jerry’s office, where he showed me his collection of keyboards, which included a Clavinet, a kind of proto-synthesizer used primarily by funk and R&B artists. Over lunch, my dad and Jerry caught up on family history, while I tried my best to pepper Jerry with questions about which rock stars he knew and what were they like (he was singularly unimpressed with them as a group, saying they weren’t that interesting and didn’t have much more to say beyond talking about what kind of guitar strings they used). Jerry was kind enough to offer to listen to a cassette recording I’d made of some songs I wrote (and merciful enough never to respond with his critique; I can only imagine how awful it was). After parting, my dad’s profound comment on the reunion with his cousin was, “I didn’t expect to pay so much for a hamburger,” and we took the train back to Long Island.

It would be years before I’d have any contact with Jerry again. The next time came via a phone call from a mutual friend – a fellow songwriter of Jerry’s named Aaron Schroeder, who had written hit songs for Elvis Presley and Gene Pitney, among others. “Guess who I’m sitting with?” asked Aaron. “Your cousin Jerry. He wants to say hi.” We spoke briefly, and agreed to renew our correspondence, which I was happy to do, given all that I had learned about Jerry – much of it directly from musicians who had worked with him or were influenced by him – in the interim.

“’Rags’. That’s what we called him. We called him ‘Rags,’” Dionne Warwick told me when I interviewed her in advance of a one-woman show she was doing at the Berkshire Theatre Festival in Stockbridge, Mass. Jerry had produced an album of Warwick’s in 1974; along with Bonnie Raitt’s Streetlights, it was one of his highest profile efforts in the pop realm. While Warwick had only good things to say about her experience working with him, and while the album was a success for her, Jerry is quoted as saying about it, “I think it’s one of the worst albums I ever made in my whole life.”

Jerry Ragovoy was a consummate music man: he wrote words and music, was a producer, arranger, conductor, piano player, A&R man (a record company talent scout), and an engineer who built the Hit Factory, one of the finest independent recording studios in New York City. He left an indelible mark on the history of R&B and soul music; a recent compilation album, The Jerry Ragovoy Story: Time Is On My Side 1953-2003 (Ace Records) includes two dozen recordings that bear his imprint and sounds like a secret history of soul music. There are few big name performers on the recording; instead, these are the originals – the jazzy, Kai Winding version of Jerry’s “Time Is On My Side,” later to be the first top 10 hit in the U.S. for the Rolling Stones; the original recording of “Good Lovin’” by the Olympics, which the Young Rascals would basically copy and ride to number one the next year.

But mostly there are the Jerry Ragovoy signatures: gospel-inflected soul vocals; deft horn and string arrangements (presumably why well-known music geeks including Donald Fagen and Elvis Costello are such huge fans); an emphasis on groove over melody. Not that his melodies don’t have their own sweep; just that for Ragovoy, as opposed to for Burt Bacharach, melody seemed to be just another form of rhythm, but one no less effective in conveying transcendent emotion. And as for groove, one need listen no further than “Good Lovin’” or Miriam Makeba’s “Pata Pata,” perhaps the first Afrobeat hit, decades before anyone coined the term.

Jerry had an uncanny ear for soulful vocalists, and he nurtured the likes of Garnet Mimms (who should be as well known as Sam Cooke), Lorraine Ellison (whose wail on “Stay With Me” could well have been the model for Joplin’s vocal on “A Piece of My Heart”), and Howard Tate (the equal of Otis Redding or Teddy Pendergrass, and whose records made with Ragovoy fed directly into the “Philly sound” of the mid-1970s).

If there remains a bit of a mystery about cousin Jerry, and how this son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants wound up creating some of the most affecting, hardest-hitting gospel-laced soul music of the 1960s, maybe the answer comes in reassessing what we mean by soul music. For Jerry, remember, was the grandson of a cantor, and what is cantorial music if not “soul music.” Certainly if, as he suggested, he was imbued with the sound of R&B through “osmosis,” he also was primed for it by being born into a milieu – indeed, into a family – that knew how to move an audience’s hearts and spirit through the keening wail of a soul singer.

An edited version of this article originally appeared in Tablet in 2011.