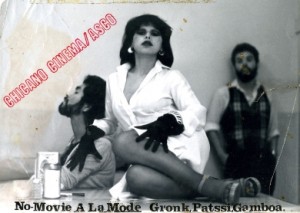

Asco, À La Mode, 1976, black and white photograph by Harry Gamboa, Jr. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC) Library. © Asco; photograph © 1976 Harry Gamboa, Jr.

(WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.) – The Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) presents Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987, the first retrospective to present the wide-ranging work of the Chicano performance and conceptual art group Asco (1972 – 1987), co-organized with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and on view starting Saturday, February 4 through July 29, 2012. Asco: Elite of the Obscure includes nearly 150 artworks, featuring video, sculpture, painting, performance ephemera and documentation, collage, correspondence art, photography (including their signature No Movies, or invented film stills), and a series of works commissioned on occasion of the exhibition.

There will be an opening reception for the exhibition on Friday, March 2, 2012, at the Williams College Museum of Art. At 4:30 p.m. there will be a walk-through of the exhibition with curators, and at 5:30 – 7 pm a reception with the artists.

Asco, Instant Mural, 1974, color photograph by Harry Gamboa, Jr. Courtesy of the artist. © Asco; photograph © 1974 Harry Gamboa, Jr.

On Saturday, March 3, from 1 to 5:30 p.m. at Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall, there will be a symposium on Asco attended by artists, curators and scholars. The symposium will feature exhibition co-curators C. Ondine Chavoya, Associate Professor of Art and Latina/o Studies at Williams College, and Rita Gonzalez, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Asco artists Sean Carrillo, Harry Gamboa, Jr., Willie F. Herrón III, Patssi Valdez; scholars Colin Gunckel, Amelia Jones, Amalia Mesa-Bains, and Mario Ontiveros.

Asco: Elite of the Obscure was organized by C. Ondine Chavoya, Williams College Associate Professor of Art and Latina/o studies and Rita Gonzalez, LACMA’s Associate Curator of Contemporary Art.

Geographically and culturally segregated from the still-nascent Los Angeles contemporary art scene and aesthetically at odds with the emerging Chicano art movement, Asco members united to explore and exploit the unlimited media of the conceptual. Creating art by any means necessary – often using their bodies and guerrilla tactics – Asco merged activism and performance and, in doing so, pushed the boundaries of what Chicano art might encompass.

Asco, First Supper (After a Major Riot), 1974, color photograph by Harry Gamboa, Jr. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC) Library. © Asco; photograph © 1974 Harry Gamboa, Jr.

The exhibition, which opened first at LACMA as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980, has received much attention in the press. “The exhibition will provide revelations and surprises for both those who are familiar with Asco’s work, as well as those just discovering it,” said Chavoya. “This is the first opportunity to expose the nearly fifteen-year output of this important yet underrated art group,” said Gonzalez. “Asco’s retrospective includes works by the artists and an extended network of collaborators, many of which have not been seen since they were produced.”

The core team of artists, Harry Gamboa, Jr., Gronk, Willie F. Herrón III, and Patssi Valdez, met in and around Garfield High School in East Los Angeles in the late 1960s. The emerging artists took the name Asco from the Spanish word for disgust or nausea, and set about expressing this shared feeling through performance, public art, and multimedia in response to turbulent socio-political issues in Los Angeles, and in dialogue with a larger international context.

Asco eventually expanded to include a larger group of artists and performers; and the exhibition highlights the contributions of the group’s many participants and collaborators, including Diane Gamboa, Sean Carrillo, Humberto Sandoval, Teresa Covarrubias, Teddy Sandoval, and Jerry Dreva, among others.

Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Asco developed a sophisticated body of work attentive to the specific neighborhoods of Los Angeles and, in particular, its urban Chicano barrios. Their work circulated more as rumor than as a documented historical account, due in part to the group’s interest in hit-and-run tactics, but even more so due to their location outside of the designated geographic centers of conceptual art production. However, the group eventually inserted themselves into a broader circuit as they became engaged with an international cast of artists involved in correspondence art.

Many works in the exhibition depict the group’s involvement in actions and staged photographs on the streets of Los Angeles. Asco’s first public performance, Stations of the Cross (1971), transformed the Mexican Catholic tradition of Las Posadas into a ritual of remembrance and resistance against the Vietnam War. The procession consisted of Gamboa, Gronk, and Herrón, who carried a fifteen-foot cross that had been constructed out of cardboard and layered with paint. The final rite was held in front of the Marine Corps recruiting center, where the costumed trio observed a ceremonial five minutes of silence before placing the cross at the door of the station and fleeing the scene.

Asco participated in a number of Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrations in East Los Angeles that were initiated by the Chicano cultural art space, Self-Help Graphics. In photographs taken by Harry Gamboa, Jr., Seymour Rosen, and Ricardo Valverde, the group’s playful iconoclasm and resistance to accepted cultural symbolism is evident.

Also included in the exhibition are photographs of actions that present the artists’ involvement in and critical response to muralism. Gronk, who had previously established himself alongside Herrón as a noteworthy muralist, performed as auteur in Instant Mural (1974), taping Valdez and frequent collaborator Humberto Sandoval to a wall. The performers then burst forth from the tape creating a transgressive image in the urban landscape. In Asco’s Walking Mural (1972) performance, a mural becomes so disenchanted with its immobility and environment that it breaks free from the wall and onto the streets.

Asco’s first unsanctioned museum display of their work occurred in 1972, when Gamboa visited LACMA and noticed the absence of Chicano and Mexican artists in the galleries. He returned later that evening with Gronk and Herrón, to sign in spray-paint an exterior footbridge on the museum campus, then came back again in the wee hours of the morning with Valdez to document what they claimed was the first Chicano conceptual art piece at the museum, which came to be known as Spray Paint LACMA (or Project Pie in De/Face). Asco cannibalized muralism as a medium, along with graffiti and later film to stage movement and possibility in exchange for static, iconic, and mythical representations.

The exhibition also features a large selection of No Movies – Asco’s signature images created for the camera that imbue performance art with a cinematic feel. As a staged event, the artists would play the parts of cinema stars, and the resulting images were then disseminated as if they were stills from “authentic” Chicano motion pictures. No Movies envision the possibility of Chicanos starring in and producing a wide variety of Hollywood films while simultaneously highlighting their relative invisibility. Essentially, Asco created images to advertise films that did not exist and circulated the imagery in a variety of inventive and innovative ways: No Movies were distributed to local and national media outlets, including film distributors, and reached an international audience through mail art circuits.

Asco’s spontaneous actions of the early 1970s were, by the late 1980s, modified into staged ensemble pieces that could highlight the interdisciplinary interests and talents of the group members.

A fully illustrated 432-page catalogue published by the Williams College Museum of Art and Hatje Cantz features essays by the co-curators, reprints of key historical documents, including interviews with the artists, and new critical essays by scholars from a variety of fields (including Maris Bustamante, David E. James, Amelia Jones, Josh Kun, Chon A. Noriega, and others).

The exhibition was organized by the Williams College Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It is made possible in part by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, and The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Support for exhibition programs has been provided by the Williams College Art Department, Latina/o Studies Program, and Lecture Committee.

One of the finest college art museums in the country, the Williams College Museum of Art houses 13,000 works that span the history of art. The museum’s principle mission is to encourage multidisciplinary teaching through encounters with art objects that traverse time periods and cultures. An active, collecting museum, its current strengths are in modern and contemporary art, photography, prints, and Indian painting.

Since its inception in 1965, LACMA has been devoted to collecting works of art that span both history and geography and represent Los Angeles’s uniquely diverse population. Today, the museum features particularly strong collections of Asian, Latin American, European, and American art, as well as a contemporary museum on its campus. With this expanded space for contemporary art, innovative collaborations with artists, and an ongoing transformation project, LACMA is creating a truly modern lens through which to view its rich encyclopedic collection.

The Williams College Museum of Art is located at 15 Lawrence Hall Drive, Suite 2 in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The museum is free and open to the public Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. Visit Williams College Museum of Art for more information.