How is it possible that the 1976 movie The Missouri Breaks was such a critical and commercial failure that most people have never seen or heard of it? After all, rarely has more talent been assembled on a single project than for this movie; the film stars Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson — both of them coming off Oscar-winning performances (the former for The Godfather, the latter for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) — and the two of them, fast friends in real life, were appearing together on screen for the first and only time. In addition, the cast includes Randy Quaid, Harry Dean Stanton, and Frederic Forrest; the score is composed by John Williams; and novelist Thomas McGuane wrote the screenplay (with help from Hollywood script doctor Robert Towne).

As if that weren’t already a veritable Hollywood dream team, overseeing the whole affair — a seriocomic deconstruction of the Western genre — was director Arthur Penn, himself coming off a series of critical and box-office successes, including Bonnie and Clyde, Little Big Man, and Night Moves. There must have been high hopes for The Missouri Breaks, and the fact that the film wound up causing not a bang but a whimper with the public could only have been hugely disappointing at the time for all involved.

What’s even more inscrutable is the fact that the film, viewed some thirty years later, holds up as a brilliantly acted and gorgeously directed movie. Penn himself is somewhat confounded by the lack of regard for The Missouri Breaks. “I like that film a lot,” he says. Indeed, in some ways the film is quintessential Penn: the outlaws are more humane than the ostensibly law-abiding, establishment figures, who are violent and cruel; the actors are given free reign to explore their roles and improvise characterizations and dialogue; the camera is used quite self-consciously in voyeuristic scenes with sudden shifts of focus; and, of course, the film contains imaginative scenes of graphic violence. “I said we have to find as many ignominious ways of shooting someone as we can find,” recalls Penn, and indeed they did, including having people gunned down while involved in the most primal biological pursuits.

So while I can’t speak for the reasons why the film failed to inspire audiences back in 1976 (although Penn acknowledges that there were “vacancies” in the script, which apparently was still unfinished when filming began), I can still pay tribute to a movie that has been on my list of all-time favorites from the first time I saw it through the fifty or sixty times I’ve viewed it since — at least twice a year for the past thirty years or so.

The Missouri Breaks is filled with countless visual and aural pleasures, including the sheer beauty of the stark Montana scenery and John Williams’s subtle score, replete with banjos, guitars, harmonicas, and electric harpsichords — unlike almost anything else he’s ever done, yet as atmospheric and suggestive as any of the bombast fueling scores for films like Jaws or Star Wars. The plot itself is familiar, almost Shakespearean: Montana rancher David Braxton (played by John McLiam) hires Robert E. Lee Clayton (Brando), based on his reputation as a top-notch regulator, to hunt down the horse and cattle thieves that threaten the foundations of his Western empire. Tom Logan, played by Nicholson, rents a small cabin and parcel of land from Braxton, who apparently sees something of himself in the young, would-be rancher. Unknown to Braxton, however, is that Logan just happens to be the leader of the gang of somewhat hapless horse thieves decimating his holdings. The story grows more complex (and Shakespearean) when Logan takes up with Jane, Braxton’s sexually aggressive daughter, and Clayton starts hunting down members of Logan’s gang. Loyalties are challenged, love gets in the way of business, and Clayton becomes a Frankenstein-like killing machine that even Braxton can’t control.

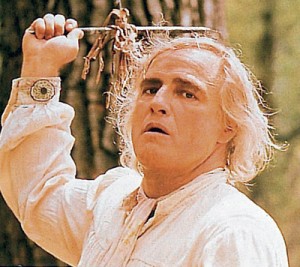

But the real beauty of the film lies in what must have been the accidental moments that Penn had the genius to catch: an obviously improvised scene between Brando and Nicholson in a cabbage patch involving a carved Mexican pistol that can be read as a passing of the torch from one actor friend to his younger protégé; Brando donning a Mother Hubbard dress before killing Harry Dean Stanton with a horrifying tool he invented to catch rabbits from atop his horse; Nicholson confronting Brando in a sudsy bathtub but not having the nerve to shoot him in such intimate confines; a singing Brando being interrupted mid-song by the sound of a urinating horse.

The film’s genius also lies in many hidden moments that only reveal themselves upon repeated viewing. It was only very recently, for instance, that my son pointed out to me that before Lee Clayton beds down for what will wind up being his last night alive, he mumbles some words that in fact are Hebrew: specifically, the opening lines from the prayer for the dead, as if Clayton knew the jig was up.

In the end, The Missouri Breaks asks of its viewers to be open to such accidental discoveries and surprises: to laugh at the absurdity of Brando’s character and his outlandish outfits and ever-changing accents and characterizations (mostly Irish, but also Indian, Southern, and as noted, a transvestite); to appreciate the role reversal between the shy, retiring Tom Logan and the sexually forward Jane Braxton; to marvel even at the sounds of the horses, whether they’re exhaling or running in a stampede.

I recently dug out my old copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Either/Or and re-read the chapter titled “The Rotation Method.” On my first reading of this as a senior in college, I was intrigued, perhaps mystified, by how Kierkegaard suggested that randomness can be grasped as a way of life, or at least as a way of viewing the world. “It is extremely wholesome . . . to let the realities of life split upon an arbitrary interest,” he wrote. “You transform something accidental into the absolute, and, as such, into the object of your admiration.”

There, in the margin right next to that sentence, I had scribbled in 1982: “The Missouri Breaks.” And that’s what I think is the secret to enjoying this movie — and any number of works of art that touch a viewer on a deep, if irrational, level. “The more rigidly consistent you are in holding fast to your arbitrariness,” continues Kierkegaard, “the more amusing the ensuing combinations will be.” So in the end, one loves The Missouri Breaks for its amusing arbitrariness, and one honors Arthur Penn for being confident enough to allow for accidents to happen as part of the creative process.

This essay originally appeared in the May 2007 issue of Berkshire Living Magazine.

8 comments for “‘The Missouri Breaks’: The Accidental Masterpiece”