For the vast majority of listeners, Warren Zevon will be forever known for his freak hit, “Werewolves of London.” While in some ways the song is quintessential Zevon — a multilayered number that functions on a literal level as a comic-horror story and on another level as a social critique (the “werewolves” variously assumed to be English punk-rockers or Southern California weirdoes) — it forever pigeonholed Zevon as a novelty artist, thereby functioning as something of an albatross around his neck.

It also left Zevon forever wanting to live up to or surpass the commercial success of the throwaway number, while at the same time causing him distress over not being taken as seriously as singer-songwriter peers such as Jackson Browne and James Taylor, to name only two of his major-league fans, a group that also included Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, both of whom collaborated with Zevon over the years.

Browne, Dylan, and Springsteen, as well as the Pixies, Don Henley, Bonnie Raitt, Pete Yorn, Steve Earle, and Dylan’s son’s band, the Wallflowers, lent their voices to Enjoy Every Sandwich, a post-mortem tribute album named after a typically wry reply to his good friend David Letterman, who, when Zevon was nearing the end of his life, asked what sort of wisdom he could offer viewers from his unique perspective as a terminal case.

Zevon had a mile-wide streak of black humor running through his songs from day one — his first album included the lament of a man beset by sex-crazed women, “Poor Poor Pitiful Me,” a hit, perhaps ironically, for Linda Ronstadt, and the eerily prescient “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead,” a first-person narrative by a character wringing every bit of hedonistic pleasure out of life while he still can.

Fans knew from various articles and interviews throughout the years that Zevon lived a life somewhat in keeping with the wild characters portrayed in songs like “Excitable Boy,” in which the character “went to dinner in his Sunday best / And rubbed the pot roast all over his chest,” and “Detox Mansion,” a comic portrayal of celebrity-chic rehab, where the coddled patients learn, “It’s tough to be somebody / It’s hard to keep from falling apart.”

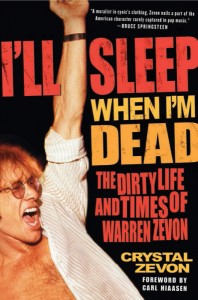

But nothing, arguably, could prepare even the most ardent fan to understand the depths of Zevon’s lifelong struggles with addiction, mental illness, and, simply, low self-esteem — an ailment he pinned on one of his characters in “Dirty Life and Times,” one of the last songs he wrote for his final album, The Wind — as outlined in gruesome detail in the exhaustive, heartbreaking oral biography, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon, by Crystal Zevon, Warren’s long-suffering wife.

But nothing, arguably, could prepare even the most ardent fan to understand the depths of Zevon’s lifelong struggles with addiction, mental illness, and, simply, low self-esteem — an ailment he pinned on one of his characters in “Dirty Life and Times,” one of the last songs he wrote for his final album, The Wind — as outlined in gruesome detail in the exhaustive, heartbreaking oral biography, I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon, by Crystal Zevon, Warren’s long-suffering wife.

No kiss-and-tell book, the story is, at Zevon’s own request, a frank portrayal of his troubled life and career, beginning with the ill-fated coupling of his Mormon mother and Jewish gangster father and running through his own lifetime of failed relationships and artistic and commercial disappointments — with a few successes, of course, thrown in for good measure.

Pieced together almost wholly in quotations from friends, relatives, and collaborators, with only a few connecting passages by Crystal Zevon, the book lacks a seamless narrative and deals only slightly with Zevon’s creative output, and, even then, usually only as it relates to the facts of his life — which, surprisingly, were more connected to his songs than anyone might have surmised.

As much as it may have appeared that Zevon was writing about fictional characters such as the mercenaries of “Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner” and the resident of a cheap motel who has to hide out because he can’t pay his bill in “Desperados Under the Eaves,” it turns out he was a confessional writer in the vein of Jackson Browne and James Taylor as much as he was a pulp writer such as Ross Macdonald and Stephen King, after whom he fashioned himself. He just had a lot more wild and crazy stuff to confess than they did.

While it turns out that Zevon was something less than the “protégé of Igor Stravinsky” as his press notices touted, he did indeed study contemporary composition with one of Stravinsky’s colleagues, and did spend some time with the master himself at an early, impressionable age. The biography alludes to Zevon’s lifelong efforts to compose his own symphony — he wrote out all the string arrangements that accompanied his songs by hand, and there are snatches of classical composition heard throughout his recordings, notably the underestimated Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School — and many of his country-rock flavored melodies aren’t nearly as simple and straightforward as they sound; his colleagues pay tribute throughout the book to Zevon’s surprising melodic and chromatic inventiveness.

(Indeed, I once worked with a piano prodigy who could not for the life of him figure out what Zevon was doing musically in one of his most gorgeous ballads, “Accidentally Like a Martyr,” the song from which Bob Dylan probably borrowed the obscure phrase “time out of mind” for his 1997 album title.)

Zevon was clean and sober for the last two decades of his life (he died from mesothelioma, a rare form of cancer, at age 56, in September 2003), but, as is typical in American pop culture, it wasn’t until he went public with his terminal illness, and then after he died, that he received his proper due (the Grammy Award-winning The Wind, released a month before his death, was his highest-charting album since 1978’s Excitable Boy).

The sardonic author of such should-be classics as “Sentimental Hygiene,” “Reconsider Me,” “Splendid Isolation,” “Hasten Down the Wind,” “Charlie’s Medicine,” and the mysteriously prophetic 1999 trilogy of death-haunted numbers — “Life’ll Kill Ya,” “My Shit’s Fucked Up,” and “Don’t Let Us Get Sick” — undoubtedly was laughing all the way to his grave, and beyond.

(This column originally appeared in Berkshire Living Magazine in May 2009 as part of the series of essays, “The Beat Goes On,” for which Seth Rogovoy was honored by the National City and Regional Magazine Association with several awards in the General Criticism category.)