By Seth Rogovoy

(GREAT BARRINGTON, Mass., May 2006) – With the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth upon us, this year we’re going to be inundated with the master’s music. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, after all, was no slouch, and immersion in the works of one of the greatest composers of all time can’t be all that painful. Mozart commands such a lofty place in the classical canon as almost to be synonymous with the very term, such that at times it can seem we’re being subjected to his work to the exclusion of all others.

So if one must somehow address or commemorate this anniversary, how, then, to do so without merely adding to a world of programming already top-heavy with Mozart? If you are artistic director Yehuda Hanani and the other good people behind the Close Encounters With Music series, based in Southern Berkshire, you do what you do best: schedule a program called “Amadeus!” featuring Mozartean chamber works, including his Quintet for Clarinet and Strings in A Major and a selection of arias, lieder, and other smaller pieces; and assemble a group of topflight musicians to perform them, including soprano Lucy Shelton, clarinetist Alexander Fiterstein, pianist James Tocco, violist Toby Appel, violinist Yehonatan Berick, and Hanani himself on cello. You pay the greatest homage to Mozart and his influence on all music subsequent to him, however, by commissioning a new piece of music intended directly to address that influence. But to whom do you turn for such a weighty take? What living composer comes to mind when you think “Mozart”?

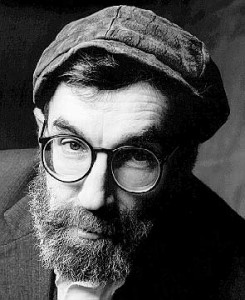

It’s too hard a question and too great a burden to pin on anyone. So instead, you simply go to one of our most creative, imaginative living composers, namely Paul Schoenfield, as Close Encounters has done for its Mozart program on May 27, 2006 (which begins at 6 at the First United Methodist Church in Pittsfield, Massachusetts – not as originally scheduled at the Mahaiwe in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where renovations have delayed the theater’s reopening until sometime late next month). and for which Schoenfield has composed a new clarinet trio as a counterpart to Mozart’s quintet.

“We didn’t want anyone to write a piece a la Mozart; this would have been pretty futile,” explains Hanani of the choice of Schoenfield for the program. “Every composer comes from some place. Every composer comes from a mix of influences.”

In Schoenfield’s case, those influences are broad and deep. As one critic, writing about Schoenfield’s Four Parables for Piano and Orchestra, put it, “Imagine James P. Johnson’s ‘Carolina Shout,’ Edgar Varese’s Arcana, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, Carl Stalling’s Concerto Populaire, and Henry Mancini’s Pink Panther theme thrown into a blender, with Harrison Birtwistle and John Williams orchestrating the whole mess. Then you get Elton John, Cecil Taylor, and Franz Liszt fighting over the difficult piano part.”

Indeed, Schoenfield’s best-known work, Cafe Music, recorded by several ensembles, including the Eroica Trio, draws variously upon early twentieth-century American, Viennese, light classical, Gypsy, and Broadway styles, all represented in a self-conscious effort to compose music that could be played both in a cocktail lounge and on the concert stage.

But Schoenfield, who began studying piano at age six and wrote his first composition the following year, is no mere pastiche artist. At the core of his compositions is a unique musical sensibility expressive of the composer’s place and time (post-World War II America) and steeped in European and American art music as well as folk, jazz, popular music, and, in particular, Jewish music.

A native of Detroit who has lived at various times in Israel, Schoenfield, who turns sixty next year, is religiously observant, and his compositions have been influenced by Jewish liturgical music as well as Hasidic songs and instrumental klezmer music. His work is represented on two recent recordings in the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music series on Naxos: Klezmer Concertos and Encores, which includes his lively “Klezmer Rondos,” and a disk devoted entirely to his work alone, Paul Schoenfield, which includes his Concert for Viola and Orchestra; Four Motets; and excerpts from his opera, The Merchant and the Pauper. These are all works that, while they may be rooted largely in a particular ethnic or folk culture, are not any more so than works by the greatest composers of the last few centuries, and they transcend their origins with the same grandeur and emotional impact of a passion by Bach or a requiem by Brahms.

Schoenfield – who studied piano with Julius Chajes, Ozan Marsh, and Rudolf Serkin, and holds degrees from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Arizona – cites Bartok as his greatest influence (he recorded the complete violin and piano works of Bartok with violinist Sergiu Luca). Like Bartok, Schoenfield is a master of taking the musical kernel of a folk melody and polishing it and expanding upon it until it is both unrecognizable and something much more sophisticated and elaborate than the original.

Undoubtedly in his absorption of jazz, Broadway, and African-American influences, as well as in his use of Jewish modalities, some will recognize a similarity to Gershwin, although Schoenfield’s Jewish references come from a much deeper and more profound relationship to the source material than Gershwin’s superficial gloss. In this, Schoenfield probably has a kinship with another contemporary composer familiar to Tanglewood audiences, Argentine-Jewish composer Osvaldo Golijov, whose How Slow the Wind song cycle was commissioned by Close Encounters and premiered at Ozawa Hall in May 2001, and whose works also bear a strong Jewish component derived from his background. Other reference points that obviously come to mind are the great Jewish-American composers Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein.

As for his relationship with Mozart, Schoenfield feels that musically there is almost none to speak of. But philosophically, he’s sure they are birds of a feather. “I think the philosophy of art back in his day is much closer to my philosophy of art today than most twentieth-century philosophy of art,” Schoenfield said in a recent conversation. “Music was entirely functional until the late nineteenth century. And when he wrote The Marriage of Figaro, it wasn’t to educate people about existential truths, other than that happiness is important. And there’s a certain religiosity in his work that’s been lost. Bach said all harmonies should be for the glory of God; everything else is just the piddlings of the devil.”

Schoenfield was still working on his trio when we spoke a few weeks ago and couldn’t say much about its shape. But he did let on that the starting point for his piece is a few movements from Figaro – he even sat at the piano and illustrated how he turned on melodic passage into a bouncy tarantella. “I’ve set a lot of folk songs to music, where I use the folk song as the starting point,” he said, “and at the end the folk song might not be recognizable.”

Says Hanani, “This is a tribute to Mozart; not an attempt to simulate him. Paul’s going to write from deep in his psyche. Things will come out and reflect his world. But it will also tell us waht he feels and thinks about Mozart.”

Schoenfield eschews the notion that composition should be the personal expression of the composer to the exclusion of or at the expense of the listener. “I always have a problem with that,” he says. “The last thing I need to do is express my depression or anger to the world. What’s the point of it? I think Mozart would have felt the same way. The other month I was listening ot the Second Schnittke quartet, and I had a vision of being tied down to the sidewalk and having people walking by and vomiting on me. It’s a masterpiece to me, but I wouldn’t want to vomit on people. I’d rather take ipecac to accomplish my vomiting.”

Given his opposition to the prevailing belief that musical composition is an act of personal expression, Schoenfield constantly questions the purpose of the contemporary composer. “Except maybe for film music,” he says. “I always find if I can make people leave a room feeling a little happier, I think that’s the best I can hope for.”

This column originally appeared under the rubric of “The Beat Goes On” in Berkshire Living Magazine in May 2006. Seth Rogovoy garnered several awards for General Criticism for this series from the National City and Regional Magazine Association. This column was one of the submissions for the award.