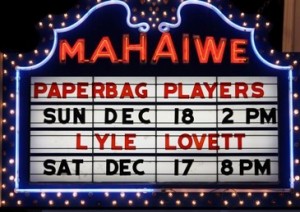

MAHAIWE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER

Lyle Lovett and his Acoustic Group

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Review by Seth Rogovoy

(GREAT BARRINGTON, Mass.) – There are still a few performers out there who work hard for their money, who equally value craftsmanship and entertainment, who continue to challenge themselves and their audiences, who boast integrity – musical and otherwise – and who seemingly still love what they do after doing it for more than thirty years. And from the view from the audience at Lyle Lovett’s generous, nearly three-hour concert at the Mahaiwe on Saturday night, count Lovett among the dwindling few who not only adhere to all these criteria, but thrive on it and set the bar high for the rest of those who fall short in one way or another as consummate performer/entertainers.

Having worked his way up the musical food chain the hard way – with lots of gigging in bars and small folk clubs while honing his craft at least since his college days at Texas A&M in the late 1970s, and without any apparent non-musical gifts to give him a leg up above the competition (not to the manor born; hardly a sex object, although his odd, quirky looks including his Erasehead-style hairdo may possibly have worked in his favor – at least enough at some point to snag Julia Roberts for awhile, and, according to a female friend in the audience at the Mahaiwe, over the course of an evening, he actually morphs into a latter-day Elvis Presley by the time the concert is over), unless one counts his incisive intelligence (he majored in German and journalism in college, and I do believe that early on he enjoyed a stint in that rarefied profession of music critic), Lovett made his arrival in the late-1980s as an uncategorizable artist who blended country, jazz, blues, Western swing, bluegrass, novelty, classic pop, early rock ‘n’ roll and that uniquely Texas brand of contemporary folk music parlayed by contemporaries and precursors including Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Eric Taylor – all of whom, it should be said, Lovett has far surpassed.

Uncategorizable, that is, until some marketing genius came up with the catch-all term “Americana,” which no one embodies more than Lovett himself, as he displayed on Saturday night in a wide-ranging program that tied together the disparate strains of American genres into a blended whole that was less Americana and more Lyle Lovett, in the same way that Randy Newman – another singer-songwriter deeply rooted in American traditions who Lovett closely resembles in sensibility if not in style – has carved out his own unique niche in the American pop canon.

Lovett was nearly perfect at the Mahaiwe. One hesitates to dissect or deconstruct his concert too much, thereby taking some if not all of the fun out of it, but suffice it to say that he is a master, presumably a control freak who makes it all look so offhandedly effortless. He knows a few secrets: surround yourself with the best musicians; pace your show – especially if it’s going to go on for nearly three hours (and at ticket prices ranging from $70 to $100, you’d best play for nearly three hours to give your fans their money’s worth, although it really is more about quality than quantity); be generous (to your audience, to your fellow musicians); and give of yourself.

Lovett originally came to fame as the leader of his Large Band (it wasn’t big, it was large), so that even though he was backed on Saturday night by five musicians, with the exception of the drummer (more on him in a minute), all string players, making this something of a string-band ensemble, fans were treated to something of an intimate evening with Lovett.

And he made the most of it, with terrific between-song patter – the guy could practically be a standup comedian in the vein of Steven Wright, with his faux-stream-of-consciousness observations, but also with his very sincere running commentary on the theater itself – he paid tribute to the Mahaiwe as theater, the restoration efforts, the audience for its support, and even the Mahaiwe staff for the fine spread they laid out for Lovett’s cast and crew (prepared by next door’s Castle Street Cafe).

Lovett clearly took the time to inform himself about the history of the venue, even referring back to its previous incarnation as a movie theater that lacked heat. Contrast this with performers who often have no idea what town they are in, much less what stage they are on.

As for those musicians: Lovett bookended himself with bluegrass-based singer-players Luke Bulla on fiddle and Keith Sewll on guitar and mandolin, who dazzled with their virtuosity. Playing electric standup bass was Viktor Krauss, who originally came to fame playing bluegrass with his sister, Alison Krauss. Lovett’s steadfast musical partner, John Hagen, is still by his side on cello and occasional vocal (and straight-man duties).

As for those musicians: Lovett bookended himself with bluegrass-based singer-players Luke Bulla on fiddle and Keith Sewll on guitar and mandolin, who dazzled with their virtuosity. Playing electric standup bass was Viktor Krauss, who originally came to fame playing bluegrass with his sister, Alison Krauss. Lovett’s steadfast musical partner, John Hagen, is still by his side on cello and occasional vocal (and straight-man duties).

But the secret weapon here was none other than Russ Kunkel, the drummer par excellence who drove the beat for so many of Lovett’s precursors in the 1970s, including Harry Chapin, Jackson Browne, Crosby Stills & Nash, Bob Dylan, Dan Fogleberg, Linda Ronstadt, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Carly Simon, Seals & Crofts, Neil Young, Warren Zevon, and perhaps for whom he is known best – the Berkshires’ own James Taylor. Kunkel added an extra bit of kick and power to the arrangements, just enough color and drama without overdoing it to push the music to the edge of rock ‘n’ roll.

Lovett, as noted, was a charming frontman, and no slouch on guitar himself. Like Randy Newman and Bob Dylan, he uses his own vocal limitations to his own advantage, and the achy, yearning quality inherent in his voice only adds character to his twisted narratives of murder and betrayal. In addition to playing all of his best-known tunes – “Here I Am,” “If I Had a Boat,” “She’s Already Made Up Her Mind,” “L.A. County,” “She’s No Lady,” “That’s Right (You’re Not from Texas),” “Private Conversation” – he paid tribute to several of his influences, including Buddy Holly, Townes Van Zandt, and even the Grateful Dead, with a stirring, haunting version of “Friend of the Devil,” which, at least for this listener, having heard that song hundreds if not thousands of times over the years, uncovered hidden nuances in the song that made a strong case for it as an all-American classic.

And that, as much as anything, was one of Lovett’s greatest accomplishments in a near-perfect night at the Mahaiwe.

Seth Rogovoy is an award-winning music critic.