Shakespeare & Company

Satchmo at the Waldorf

Written by Terry Teachout

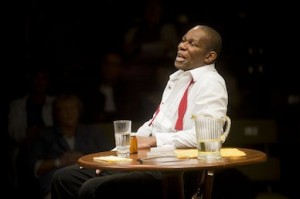

Starring John Douglas Thompson

Directed by Gordon Edelstein

Review by Seth Rogovoy

(LENOX, Mass., August 17, 2012) – There is nary a wrong nor a false note played in Terry Teachout’s Satchmo at the Waldorf, starring John Douglas Thompson as Louis Armstrong, directed by Gordon Edelstein, and running at Shakespeare & Company through September 16, 2012, before it heads to Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, where Edelstein is artistic director, for a run. And it’s not just because, as Teachout — an Armstrong biographer as well as one of America’s most esteemed jazz and theater critics – has Armstrong say, “There are no wrong notes in my music.”

Rather, it’s because Teachout has written a pitch-perfect script that accomplishes the nearly impossible – rendering Armstrong’s life, times and music in all of its American triumph and tragedy in the course of only 90 minutes and through an innovative theatrical device that has Thompson playing both Armstrong and his lifelong manager, Joe Glaser, and dramatizing the intense bond that tied the two together in an almost impossible Gordian knot until, as Teachout’s Glaser says several times to the musician, “I’m Louie and Louie’s me.”

While on paper, the premise of the evening is dubious – Armstrong is in his dressing room after a performance at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City in 1971, the last year of his life, and we, the audience, happen to be there, and he decides to take us into his confidence and spill the beans about his life and career, and in so doing, work out the demons and doubts that have plagued him about the artistic choices he has made and the authenticity of his friendship with Glaser – in Thompson’s hands, doubt is suspended almost instantaneously, and we are with him, and believing in him and the premise the entire time.

It’s a tour de force performance, which at times has Thompson turning back and forth on a dime between playing Armstrong and Glaser. It’s a dazzling exhibition of the actor’s art, but always in the service of Teachout’s script and the drama and conflict inherent in the story, which embraces the history of 20th century American race relations, the evolution of jazz music, Black-Jewish relations, and the question that plagued Armstrong and continues to bother some – did he in some way set back the course of black Americans through his willingness to play ball with his increasingly white audience as one of the great entertainers of the modern era? Or, as fellow jazz trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis apparently would have it, was he the ultimate Uncle Tom, and was his relationship with Glaser his original sin – did he sell his soul, or his creative birthright, for a pot of Glaser’s gold, only to see it taken away from him at the end?

This is heavy stuff, but it all comes out through vivid scenes “between” Thompson-as-Armstrong and Thompson-as-Glaser. Having the same actor play both, in this case, merely magnifies the conflict while underlining the ultimate point – that while seemingly one or both of them must have betrayed the other (or himself), in fact, both Armstrong and Glaser did the best that they could, for himself and for each other, given forces that exerted pressure on them that were beyond their control.

In the course of the evening, we are treated to a musicological lesson by Armstrong himself, as he reveals that the scaffolding for one of his all-time great improvisations – the opening bars of “West End Blues” – was actually patterned after grand opera. In this same, short tune, Armstrong also planted the DNA for what would become known as “scat singing” – the wordless vocals that mimic musical instruments played by a jazzman.

Glaser may have been Armstrong and Armstrong may have been Glaser, but John Douglas Thompson is both of them. He brings them to life in all their self-conflicted pathos and glory – as well as in their humor and love of language, the more off-color the better. Thompson’s characterizations are vivid, and one marvels how he is able to shift seemingly effortlessly between them, sometimes in a matter of mere words.

And even then, without giving too much away, he briefly throws in a third character, giving a perfect rendition of a pompous, radicalized Miles Davis, who was filled with as much hate as Armstrong was filled with joy.

It’s hard to imagine how Satchmo at the Waldorf is not going to be a huge hit, destined for Broadway with John Douglas Thompson at the helm. There is so much depth and passion in this story, so many overtones of love and betrayal, so much humor, and so much heartache. It’s a great American story, and ultimately, there is so much of what made the American public love Louis Armstrong inherent in Satchmo at the Waldorf. And that’s why, like “Hello, Dolly” did, this play is going straight to number one.

Seth Rogovoy is an award-winning music and cultural critic and the author of Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet.