Benjamin Clementine

Hunter Center

MASS MoCA

North Adams, Mass.

October 15, 2016

by Seth Rogovoy

(NORTH ADAMS, Mass.) – About once every few years, if I’m lucky, I see a performer for the first time who leaves me breathless and reminds me why I got into this business in the first place. Over the years, these artists have included Bruce Springsteen, David Byrne, Lyle Lovett, Ani DiFranco, and Simi Stone. On the basis of his magnificent performance at MASS MoCA on Saturday night, add Benjamin Clementine to that rarefied list.

Still almost an unknown in the U.S., the London-based Clementine is a hero back home, where he won the Mercury Prize last year – less like winning a Grammy Award and more like winning a Pulitzer. Clementine’s superhuman vocals; his shimmering piano style; and his poetic, confessional lyrics, put him in the great tradition of troubadour singer-songwriters, but less in the folk vein and more in the tradition of jazz, soul, cabaret and theatrical pop. To grossly simplify it, he’s like the bastard offspring of Nina Simone and Rufus Wainwright, but also wholly his own – born fully grown as a unique persona.

And what he proved Saturday night is that the critical acclaim for his recordings is more than matched by his live performance. His voice is even better live than on record. One of the charms of hearing his recordings is how naked and vulnerable he sounds, which sometimes leads to cracks and near-misses in pitch control. But in concert, he was totally in control and then some, even more dynamic and brave in the impossible vocal leaps and swoops around the octaves, facing down the challenges he presents himself with the grand melodies he composes, which veer from simple repetitive tones, almost rhythmic and staccato more than melodic, to semi-operatic passages that boast the impact of a symphony orchestra.

In contrast to his bold, effusive music, Clementine boasts an adorably low-key stage persona. Through a gauzy scrim of shyness, he utters endearingly simple observations that are filled with wit and layers of irony and gee-whiz bemusement. “America,” he said, several times, and in that simple word he said volumes about the dynamic in that room, at that moment, Clemetine vs. America, England vs. America, the world against Donald Trump, Clementine with this particular audience, and on and on. “America likes more bass,” he said, referring to his solo voice and piano setup onstage, before proceeding to thunder through another rock drama before this capacity crowd that turned out for the culmination of a daylong celebration of the opening of artist Nick Cave’s new site-specific installation, “Until.” (Cave reportedly chose Clementine to perform on Saturday night.)

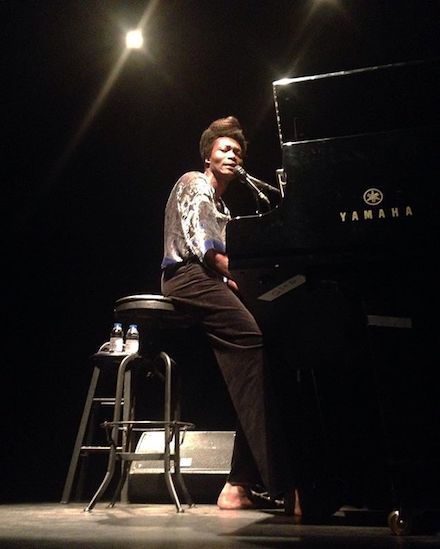

Clementine is also a striking presence. I’ll leave it to others to gush about his gorgeous looks and his impossibly sculpted cheekbones, but the tall, lanky performer sat on a high barstool with his long arms hanging almost vertically down to the piano keyboard. It seems like an impossibly difficult way to play the instrument – the conventional mode of attack is at a 90 degree angle from one’s body, this must have been more like 10 or 15 degrees – but it certainly didn’t get in the way of Clementine making the most of the instrument, pounding out lush glissandos and arpeggios that gave Rachmaninoff a run for his money.

Clementine’s songs are raw wounds drenched in the beauty and sadness of his vocals and minor-key based melodies. His vocal range, from deep bass to piercing high notes, gives him a huge palette from which to paint his lightning strikes of emotion, and his forceful balladry doesn’t forsake rhythm, either – you could often hear the toe-tapping of your neighbors in the audience. Clemetine boasts a carefully controlled but often-wielded vibrato; at times his playing and voice merged into a kind of shimmering, harplike sound.

Clementine seemed to channel the spirit of the aforementioned Nina Simone, as well as Billie Holiday, Little Richard, Ray Charles, Joan Armatrading, Tori Amos, and David Bowie. He played a Nick Drake tune, offering a hint of where he seems himself in the pantheon of moody English singer-songwriters, and even though he could brew up a tempest of music and emotion, he also maintained a sense of ethereality throughout – he simply at times doesn’t even seem human, owing to his super powers, his overflowing talent in abundance, and his shocking physical presence.

Oh, and lest I leave out another essential detail, he played barefoot.

Seth Rogovoy is the author of “Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet” (Scribner, 2009)