by Seth Rogovoy

This article was originally published in Hadassah Magazine in the April/May 2015 issue. Subsequently, I was awarded a 2016 Simon Rockower Award from the American Jewish Press Association for excellence in arts and criticism for this piece.

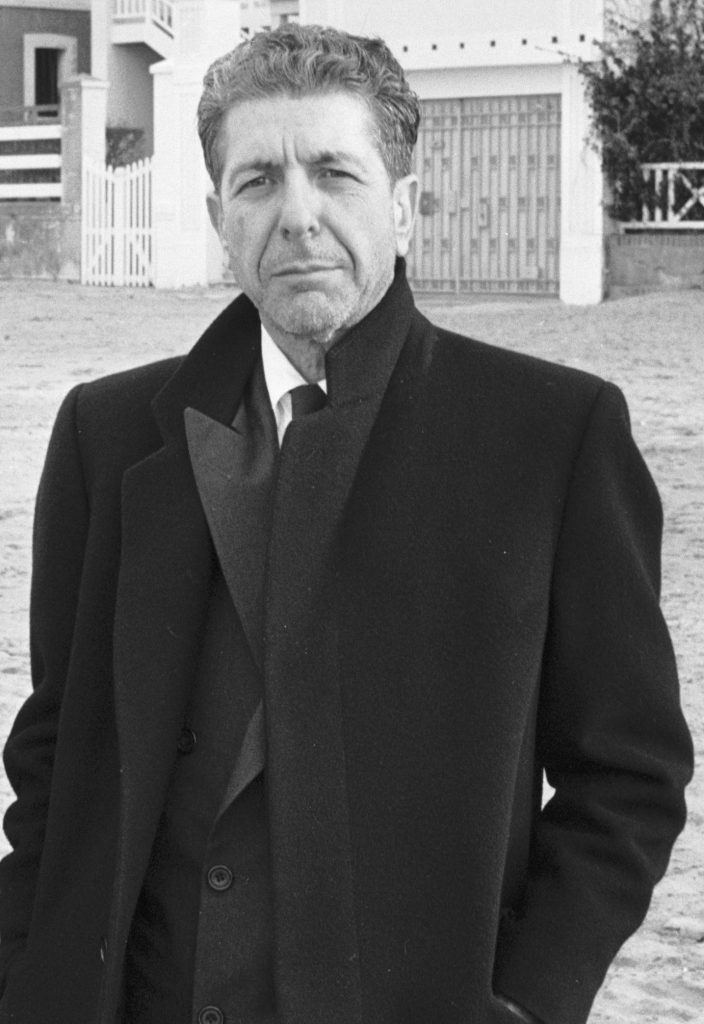

ARTIST OF THE YEAR, songwriter of the year, and “fan choice” of the year. Katy Perry? No. Justin Bieber? Think again. An improbably 80-year-old, gruff-voiced Jewish grandfather by the name of Leonard Cohen went into the Juno Awards – Canada’s answer to the Grammy Awards – in March with nominations in these three categories

In some ways, it’s no surprise, as Cohen has been on a quite a roll these past few years, selling out theaters, arenas and stadiums around the world and releasing some of the bestselling albums of his nearly 50-year recording career. Along the way he’s had his personal and professional ups and downs, on the one hand seen as one of the greatest voices of his generation, then consigned to the back shelf, then championed by another generation, only to leave it all behind and live in a Zen monastery on a California mountaintop for five years. Then, upon his return to civilization, he discovered that his longtime manager and erstwhile friend had stolen all his money, and once again he had to hit the road to earn a living.

Fortunately for Cohen, he was always something of an oddity – an elder statesman of pop music even when he released his first album at age 33. Never having dealt in fads or trends, always sticking to his straightforward style, never having dumbed down his lyrics, he could never be accused of betraying himself. And his subject matter – love, sex, God, depression, ecstasy, and spirituality, not necessarily in that order – have made Cohen something of a latter-day prophet, one whose work holds healing, even life-changing, properties for his fans.

Take Liel Leibovitz. When he was 13, Liebovitz’s world collapsed when his father was revealed to be the “Ofnobank,” or motorcycle bandit – Israel’s celebrity criminal, who robbed nearly two-dozen banks in a two-year spree. At bar mitzvah age, Leibovitz saw his father go to prison, and suffered the notoriety that came along with the case, since his father was a scion of one of Israel’s wealthiest and most powerful families.

His friends tried to comfort Liel with gifts of music, mostly original – and forgettable — mixes of bad pop on cassettes. But one tape was a complete album called “Songs of Leonard Cohen.” Intrigued, and figuring it might be something Jewish, Liel played the tape, and what he heard changed his life.

“I didn’t understand the lyrics, because my English was shaky. But something about the voice was telling me truth, and it had a rabbinic presence throughout my life,” says Leibovitz, now 37 and a resident of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where he is a senior editor for the online Jewish magazine Tablet. Over the years, the lessons imparted through Cohen’s songs, writings, and biography got Leibovitz through tough times.

The Montreal-born rock poet who was president of the Jewish fraternity at McGill University remains Leibovitz’s touchstone to this day, culminating in the publication last year of “A Broken Hallelujah: Rock and Roll, Redemption, and the Life of Leonard Cohen” (W. W. Norton & Company), Leibovitz’s midrashic exploration of Cohen’s life and work that draws from a wide range of sources and is filtered through the author’s keen understanding of Cohen’s own relationship to his Jewishness.

Cohen’s name offers merely a hint of his yikhes — on both sides of his family he is descended from rabbinical scholars, and his ancestors were integral to the founding of Montreal’s modern Jewish community. Like his contemporary and fellow rock-poet, Bob Dylan, Cohen grew up at the very center of his town’s Jewish communal life, with a strong Jewish home life that included a grandfather who studied Talmud every day and, in Cohen’s case, quizzed him on the Book of Isaiah.

Those lessons stuck with the budding poet, and the legacy of that youthful education in the Bible and the Prophets infuses his work, giving it the extra power and gravitas that comes from being immersed in the prophetic. “The prophet understood that humankind’s spiritual and sexual yearnings were intertwined,” writes Leibovitz, and this equation gave Leonard Cohen the basic thematic material for a lifetime’s worth of poems and songs.

Cohen told an interviewer in the mid-1980s, “I think that I was touched as a child by the music and the kind of charged speech that I heard in the synagogue, where everything was important. The absence of the casual has always attracted me.” The “absence of the casual” may well be one of the singular characteristics setting Cohen’s work apart from his contemporaries.

Cohen came to songwriting relatively late, at the age of 33, at a time when the countercultural catchphrase was “Don’t trust anyone over 30.” Cohen had first made his mark as a poet and novelist in Canada in the early 1960s, with poetry volumes titled “The Spice-Box of Earth,” a reference to the Havdalah besamim, and “Flowers for Hitler,” which in poetry did for Adolf Eichmann what Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem” did in prose – made him out to be a pathetic but ultimately banal cog in the wheel of destruction.

Frustrated by his lack of an audience beyond the Canadian literati, however, and inspired by the example of Bob Dylan – whose mission was similarly based in the Hebrew prophetic tradition — Cohen saw a more efficient way to get his work across, and so he picked up his guitar and set his poems to music. One of his very first songs, “Suzanne,” was recorded by Judy Collins and included on an album of songs by Dylan, the Beatles, and Randy Newman. Thus in short order did Cohen find himself near the top of the singer-songwriter pecking order.

Cohen’s songs are intensely personal and introspective; he drew deeply from the well of Torah for themes, symbols, and inspiration, although much of this aspect may have been lost on the vast majority of listeners. Cohen’s midrash-in-song works in several ways. It can be an almost literal paraphrase of a Bible story, such as with “The Story of Isaac,” in which he sings, “You who build these altars now/ To sacrifice these children/ You must not do it anymore,” or in his hymnlike recitation of the key line from the Book of Ruth: “Whither thou goest I will go/ Whither thou lodgest I will lodge/ Thy people shall be, My people.”

Cohen can base a poetic riff on liturgy, such as in “Who By Fire?,” based on the Yom Kippur prayer Unetanah Tokef, which he renders as, “And who by fire, who by water/ Who in the sunshine, who in the night time/ Who by high ordeal, who by common trial…/ And who shall I say is calling?” His 1984 collection of 50-odd prose poems, “Book of Mercy,” can be read as a contemporary rewrite of King David’s Book of Psalms.

Sometimes Cohen’s Jewish allusions can be so subtle that not only his audience but also fellow singers miss his intent. His well-known tune “Dance Me to the End of Love” has sparked numerous cover versions, with its infectious waltz-like rhythm and Central European-inspired cabaret melody. There’s a deeply mordant irony underpinning the song, however; when Cohen sings, “Dance me to your beauty with a burning violin,” he’s talking about Auschwitz as much as the dance hall.

Then of course there is Cohen’s most famous song, “Hallelujah,” which begins, “I’ve heard there was a secret chord/ That David played, and it pleased the Lord….” Cohen’s “Hallelujah” has pleased over 300 other artists who have recorded versions of the tune since it debuted on his 1984 album, “Various Positions.” The song has also been the subject of a BBC Radio documentary and a full-length book – one wit called it “the ‘White Christmas’ of dark and moody songs.” In some sense, Cohen’s entire career can be seen as a lifelong attempt to find that secret chord about which he sings.

For the most part, Leonard Cohen has been seen, somewhat correctly, as the bard of gloom and doom – his recordings have even been called “music to slit your wrists by.” But there’s something much deeper than depression – from which Cohen has suffered throughout his life – buried in his songs. There is an exploration of the human predicament – brokenness, or, as the mystically inclined Cohen put it in “Anthem,” a song on his critically acclaimed 1992 album, “The Future,” “There is a crack, a crack in everything/ That’s how the light gets in,” an allusion to the Creation story of Lurianic Kabbalah.

This darkness, this sense of all-pervasive gloom, has stood in the way of mass popularity in his adopted home of the United States. The rest of the world, and Europe in particular, however, has always embraced Cohen and understood that he speaks with the authority of one who must be heard. Leibovitz ventures an explanation for the disparity between Cohen’s popularity at home versus the Old World:

“America’s a teenager” in comparison with Europe, says Leibovitz. “When they hear reference to ‘a broken hallelujah,’ they say, ‘Well then, let’s fix it.’ When they see the moon, they say, ‘I want to go there.’ America is not built for a statement like, ‘There’s a crack in everything/ That’s how the light gets in,’ which is so spiritually and antithetical to everything it’s about…. On the other hand, it’s easy to see how a continent recovering from catastrophe would embrace a man like that, whereas America says ‘That’s depressing.’”

One thing Cohen has never done is change his approach. His sound has slowly evolved to include more keyboards, rhythms, harmonies and other musical colors, but ultimately the song remains the same. Cohen never went disco, new wave or Las Vegas, nor has he ever dumbed down his material or recorded an album of Frank Sinatra standards.

And surprisingly, as he’s aged – Cohen turned 80 last year, making him by far the oldest continually touring and recording pop star – his voice has gotten better and his comfort level onstage has drastically improved, to the point that he now sells out multiple dates not only in European cities but even in the U.S. (In earlier years, Cohen dreaded giving concerts almost as much as touring itself, and could only do so reportedly with the aid of copious quantities of drugs or alcohol.) Through sheer persistence, it seems, Cohen has finally found an American audience that appreciates seeing things Cohen’s way – the old way, the Biblical way, the prophetic way.

Even at 80, Cohen shows no signs of stopping. Last year’s album, “Popular Problems” – which includes songs with titles such as “Samson in New Orleans” and “Born in Chains” — was his bestselling ever. Released two days after his 80th birthday, it reached No. 1 in 29 countries on the iTunes chart, garnering Cohen his first ever No. 1 album in Austria and Switzerland, becoming the best-selling album of the week in Israel, and also topping the charts in Belgium, Canada, Holland and Portugal. (It peaked at no. 15 in the U.S.)

Nor does the man who once wrote, “I’m the little Jew who wrote the Bible” show any sign of giving up his particular kind of prophecy – highly personal, self-mocking, yet apocalyptic all the same, as in the new song “Almost Like the Blues”:

Though I let my heart get frozen

to keep away the rot

my father says I’m chosen

my mother says I’m not

I listened to their story

of the gypsies and the Jews

It was good, it wasn’t boring

It was almost like the blues

There is no G-d in heaven

There is no hell below

So says the great professor

of all there is to know

But I’ve had the invitation

that a sinner can’t refuse

It’s almost like salvation

It’s almost like the blues.

Cohen himself has always identified his work as a kind of spiritual mission. As he told Arthur Kurzweil in a 1993 interview (collected in “Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters,” edited by Jeff Burger), “When they told me I was a Kohayn, I believed it. I didn’t think this was some auxiliary information. I believed. I wanted to wear white clothes, and to go into the Holy of Holies, and to negotiate with the deepest resources of my soul.”

Leonard Cohen’s American moment might finally have arrived. Explains Leibovitz, “His voice is what we’ve been waiting for because his message is one we’re finally ready to hear. A triumphalist young nation in the throes of perpetual orgasm doesn’t listen to Leonard Cohen; a middle-aged nation having gone through several painful wars, a breakup, awakenings, licking its wounds after 9/11.… It’s finally ready to hear Leonard Cohen, and to listen.”

Seth Rogovoy is the author of Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet (Scribner, 2009).