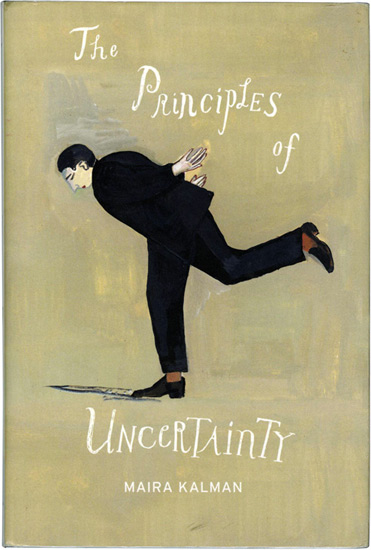

The Principles of Uncertainty

by John Heginbotham and Maira Kalman

Jacob’s Pillow Dance

Becket, Mass.

August 26, 2017

Review by Seth Rogovoy

(BECKET, Mass.) – The curtain came down this past weekend in the Doris Duke Theatre at Jacob’s Pillow Dance on the world premiere of “The Principles of Uncertainty,” a wild and wacky collaboration primarily between choreographer John Heginbotham and illustrator and author Maira Kalman, with significant contributions from music director Colin Jacobsen and his ensemble, the Knights; assistant director Daniel Pettrow, who also performed in the piece (as did Kalman, but not Heginbotham); lighting designer Nicole Pearce; and, of course, the dancers of Dance Heginbotham.

Everyone’s roles are not easily assigned in the work – in addition to writing the “book,” as it were, for the piece (based on her work by the same name), Kalman also designed the sets and costumes, which seemed to pop out right off the page of a Kalman cartoon. Heginbotham is also credited as “director,” because, well, although this work was premiered at Jacob’s Pillow Dance, it is a whole lot more than just dance. “Dance-theater” doesn’t even begin to capture it, but more on that in a moment. The musicians weren’t merely a pit orchestra accompanying a show – they were fully onstage and as present in the show as anyone else.

Such a production is not unexpected from Heginbotham, who, although he came up the ranks as a dancer, mostly with Mark Morris Group, has as a choreographer shown himself to boast an exuberant restlessness with form, each time out not merely making a new dance but entirely reinventing the canvas and palette of his work.

The notes for the program suggest that the piece “is based on Heginbotham and Kalman’s shared interest in the passage of time and its relation to the seemingly mundane objects and experiences that make up daily life.” Maybe so, but that’s a rather lifeless description of an evening-length work that unveils in a series of vignettes that range from comic to tragic, mostly in service of pleasure, “uncertainty,” humor, and an overall sense of the absurd.

For example, Nietzsche is invoked several times as a kind of haunting spirit over the proceedings, but not without tweaking the German philosopher by misspelling his name a few times in Kalman’s superb animations. Before the metaphorical curtain even drops on the performance, the audience is enrolled in the amusement, taking seats that have been labeled with whimsical words and expressions such as “cozy,” “eclipse,” “tisane,” “book shop,” and, my favorite from those I could read, “cold feet,” which has layers of meaning in a dance venue and at a show that challenges an audience intellectually and otherwise.

For example, Nietzsche is invoked several times as a kind of haunting spirit over the proceedings, but not without tweaking the German philosopher by misspelling his name a few times in Kalman’s superb animations. Before the metaphorical curtain even drops on the performance, the audience is enrolled in the amusement, taking seats that have been labeled with whimsical words and expressions such as “cozy,” “eclipse,” “tisane,” “book shop,” and, my favorite from those I could read, “cold feet,” which has layers of meaning in a dance venue and at a show that challenges an audience intellectually and otherwise.

The modular set, consisting of benches, seats, a hutch, and a big box, most in a contemporary, minimalist Scandinavian style, allowed for an ever-changing canvas on which to play out what on some level must have emerged from or been purposely intended to be a conversation between Kalman and Heginbotham. The former, who sat upstage on a bench for most of the program, intoned short phrases that often seemed to be historical weather reports, such as one for that fateful August day in Pompeii, when residents were warned it was going to be “hot and humid with a chance of showers.” Showers, indeed. The word “ERUPT,” featuring trembling letters, was projected on the white backdrop, and the ensemble played “Vuci mia cantannu via” by Italian film composer Andrea Guerra.

There was, of course, dancing throughout, although it should more correctly be thought of as movement. The dancers (John Eirich, Lindsey Jones, Courtney Lopes, Weaver Rhodes, Macy Sullivan) were a versatile corps, required in order to pull off Heginbotham’s dizzying array of stylistic moves, based in classical ballet, court and folk dance, street, yoga, acrobatics, and modern. Their disarmingly ordinary appearance, without any sense of uniformity among them – partly the result of the costuming, but also one assumes as per Heginbotham’s intentional, curatorial choice – was belied by their strength and precision, as well as their unique gifts as individual actors, of which Heginbotham made the most.

Among the moments that stood out: The dancers are standing still while collectively holding up a fish tank. Out of the stillness, suddenly their feet began to move, as if they couldn’t repress the desire to dance (and to provoke laughter) – or perhaps, in this case, the desire to swim like the fishes that might have inhabited the tank. It was beautiful.