I forget where or exactly when I caught wind of this book – it may have been just a few weeks ago, in an advertisement in a literary journal – but it was the title that really grabbed me at first. “Oh good,” I thought to myself ironically. “Finally, a how-to book I can really use.” (I need no how-to; I’ve been figuring out how to be depressed—or how to live with depression—pretty much my entire life.)

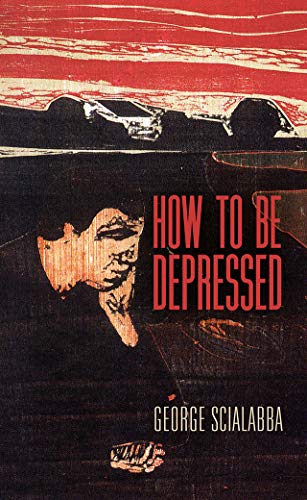

So I took a chance on How to Be Depressed by George Scialabba (University of Pennsylvania Press) partly because of the title alone, without reference to any reviews – something I never do. It undoubtedly helped that the jacket cover is a detail from a work by my favorite painter, Edvard Munch, whose entire opus looks to me like one lifelong portrayal of anxiety and depression, and an entirely accurate one at that. So I was sold on the book before I even had it in hand.

I read How to Be Depressed in two sittings. It is a fascinating book that is mostly made up of various therapists’ notes spanning a half-century of sessions treating the author for chronic depression. The notes, which make up the body of the book’s narrative, are bookended by Scialabba’s introduction, a transcript of an interview conducted by Boston media celebrity Christopher Lydon, and a cheeky conclusion by the author called “Tips for the Depressed.”

The book is remarkable for its candor, and I don’t think I’ve ever read such a clear and transparent explication of what it is like to live as a depressed person. But what is even more remarkable is how the doctors’ notes, only slightly edited by Scialabba, work to tell the story of Scialabba’s life and depression, including his upbringing, his troubled college years, his regimen of ever-changing medications, and his lifelong struggle to self-actualize—to become the public intellectual that he so desperately wants to be and that deep inside he knows he can be, and is only prevented from becoming due to his depression. Somehow, these mere notes turn out to be gripping reading—not unlike a detective novel, wherein the parade of therapists (as well as the patient) are forever in search of the answer to the questions posed by Scialabba’s depression—what is its nature? Why does he have it? Can it be successfully treated and cured? And, along the way, can Scialabba ever figure out just who exactly he is and what to do with his life?

Scialabba is unduly modest at times—one wouldn’t know that he had a regular column for the Boston Globe for awhile; that he had published prodigiously in newspapers, magazines, and journals including the Nation, the New Republic, and the Washington Post; and that he was the subject of a profile in the New Yorker, aptly titled “The Private Intellectual,” which hailed him as a “dauntingly well read … master of the book review.” The Harvard- and Columbia-educated writer even received the first Nona Balakian Excellence in Reviewing Award from the National Book Critics Circle. He’s far from his image of himself as chopped liver, although that perhaps has something more to do with his 35-year-long day job as a clerk at Harvard, rather than the professor he might have been had he been dealt a slightly different deck of cards.

Of course, in the end, Scialabba proves victorious, in that you are reading the book that he was destined to write, one that turns out to be almost avant-garde in its ingenuity, one part Oulipo-like experiment, one part intellectual memoir. I’m sure Scialabba has other books to write, and after reading How to Be Depressed, one hopes he finds his way toward achieving more milestones. And if not, so be it – How to Be Depressed (in addition to five collections of his literary criticism and essays) serves as a worthy monument to his life of emotional and intellectual struggle, one that any depressed reader will find easily relatable and one that paints a Munch-like picture for readers without first-hand experience of the noonday demon. I hope Scialabba finds some considerable solace and comfort in that alone.