by Seth Rogovoy

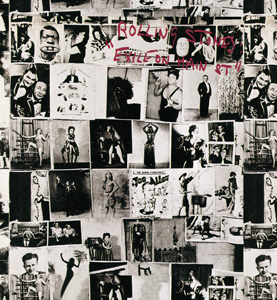

Since its release thirty-eight years ago, the Rolling Stones’s double album, Exile on Main Street, has widely been regarded as the British rock ’n’ roll band’s greatest achievement and one of the greatest — if not the greatest — rock albums of all time. Rolling Stone magazine recently called it “certainly rock & roll’s most rock & roll album,” adding that none of the other contenders “comes as close to rock & roll’s ideal synthesis of blues, country and R&B.”

It’s a dubious distinction, at that. Frankly, if I were Mick Jagger, this sort of praise would make me more than a little self-conscious, as Exile on Main Street is the least Rolling Stones-sounding album the Rolling Stones ever made. There’s little of the preening, lascivious Jagger to be found here, and his vocals for the most part play second fiddle to the instrumentalists. There’s only a modicum of Keith Richards’s signature riff-rock; Richards mostly credits fellow guitarist Mick Taylor for the creative innovations of the album.

Instead, what jumps out at a listener reacquainting himself with this masterpiece nearly four decades after its release — on the occasion of a newly remastered reissue including a second CD of previously unreleased tracks from the Exile sessions, such as they were — are the non-Rolling Stones touches, such as Nicky Hopkins barrelhouse piano and Bobby Keys and Jim Price’s New Orleans-style horns. Jagger is nearly a spectral presence for the most part, and indeed, several of the core musicians comprising the Rolling Stones at the time didn’t even play on several of the tracks.

While the writing and recording of the songs on Exile span a four-year period from 1968 to 1972, which saw the band residing in England, Europe, and the United States, the bulk of the album was recorded in France, to where the Stones had fled, as did many successful rockers of the time, from Britain’s onerous tax laws. Failing to find an appropriate studio in which to record their follow-up to Sticky Fingers, the Stones set up in the basement of Keith Richards’s rented villa Nellcôte, in Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice. Various rooms in the basement became mini-studios where musicians could practice or record, and all were wired to a mobile recording unit housed in a van parked outside that the band brought over from England.

In large part, the tracks as we hear them were pieced together by producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Andy Johns; rarely were the five band members together in one room playing through songs as a group. This is why, for example, the song “Happy” wound up being sung by Richards, who showed up early one day ready to present the song to Jagger. Instead, only saxophonist Keys and Miller were on hand, and, raring to get going, Richards laid down the basic tracks and vocal with just the three of them, with Miller at the drum kit instead of the absent Charlie Watts. Bassist Bill Wyman was even more of a no-show for most of the sessions, with many of the bottom duties falling to Richards, guitarist Taylor, and acoustic bassist Bill Plummer.

As it turned out, the informal, jam-like atmosphere totally suited the material, and in many ways, literally and figuratively, Exile on Main Street was the Rolling Stones’s equivalent of Bob Dylan and the Band’s Basement Tapes. “Turn and Frayed” seems like an overt attempt to cop the sound of the Band, whose offhanded basement-recorded efforts with and without Bob Dylan in Woodstock, N.Y., produced some of that North American group’s most significant music. No doubt the Stones had heard the widely bootlegged results of those sessions, and between Taylor’s Robbie Robertson-like licks and Price’s Garth Hudson-ish organ phrasing — to say nothing of Jagger and Richards’s country-style harmonies echoing those of Rick Danko and Levon Helm — the effort is an obvious tribute to American roots music, as is much else on the album, especially “Sweet Virginia,” “Sweet Black Angel,” and “Loving Cup” — this last number another Band-like tune driven by Hopkins’s Richard Manuel-like piano and Watts’s Levon Helm-style country-funk drumming.

Some of the songs on the original album, such as the ghostly blues, “I Just Want to See His Face” and the choral-keyboard number, “Let It Loose,” seem hardly finished (and that’s not even dipping into the re-release’s second CD of ten bonus tracks, which, much to the chagrin of Richards and Watts, Jagger overdubbed recently, thus rendering them historically incorrect). These are half-baked tracks of the sort, again, that one accepted from the Band’s Basement Tapes with the understanding that the album was never intended for official release, as opposed to Exile, which was very much intended and taken as a major statement by the Stones as the sixties became the seventies.

The Rolling Stones, of course, were always influenced by American blues and R&B — they veritably began as an R&B cover band — but what’s most significant about Exile is the manner in which the Stones shed their own essence, their very Stones-ness, if you will, in the service of the music. To wit, there are no greatest hits on this album, nothing on the order of “Satisfaction” or “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” or “Honky Tonk Woman” or “Brown Sugar,” although “All Down the Line,” which was buried on the second side of the second LP — number fifteen on the CD — recapitulates some of that sound and sass, with the sweet addition of New Orleans-style horns and some mischievous lyrics by Jagger (he repeatedly sings, “open up and swallow,” although you won’t find that phrase in any officially published lyrics, which render the phrase as “open up the throttle”).

The eighteen-song album only garnered one Top 10 hit, “Tumbling Dice,” most notable for the way in which it deconstructs its groove, preferring a lazy, funky strut to the Stones’s usual hyperkinetic march, and their concerts rarely draw upon more than one or two songs from the album.

Nearly forty years on, Exile on Main Street sounds like what it really was: an accidental album, a series of recordings of jamming by band members in various duo and trio configurations patched together with the help of overdubs applied by Jagger later on in a Los Angeles recording studio. But what the remastered, re-released version of Exile captures is a band at its most relaxed, a band not performing but simply playing music, a band, consciously or not, not making an album, but digging deep into the wellsprings of American music — blues, gospel, country especially — as a way out of the insanity that preceded the making of Exile — the psychedelic era that culminated in the tragedy of the 1969 Altamont Free Festival (where a fan was stabbed to death by Hell’s Angels security guards while the Stones played “Under My Thumb”).

The Stones weren’t alone at the time in returning to roots, or their roots. This was the same era when Bob Dylan recorded several albums of country-flavored music in Nashville; when Paul McCartney’s album Ram fit him visually and musically for the role of gentleman farmer; when the Kinks reinvented themselves as Muswell Hillbillies; and when Linda Ronstadt’s backing band went out on its own as a group called the Eagles, forever carving a place for country-rock on the top of the pop charts. The Stones, to their credit, were tapping into the zeitgeist.

Mostly though, through the chaos caused by the random arrivals and departures of the musicians, of songs that rub up against each other in jagged juxtapositions, in not very convincing attempts by Englishmen at playing American roots music, Exile on Main Street captures the second most successful pop-rock band in history at its most vulnerable and naked. The love of the music is first and foremost, and if it is served up in less than perfect renditions, it’s no less beautiful for its authentically raw and ragged quality. To some, including to this listener, it’s preferable to the overhyped hysteria of what came before and to the overproduced slickness of what would follow.

This essay originally appeared in the June 2010 issue of Berkshire Living Magazine.