For those who think the rock concept album is a thing of the past, for those who fear that in the age of the single download, the big statement is no longer the province of pop, take heart. With The Suburbs, a glorious song cycle that is novelistic in scope, the contemporary Canadian septet Arcade Fire offers hope for a vanishing art form.

Forget Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom — if you’re looking for the great artistic statement about American life in this moment, you’d do better to live with The Suburbs for a few weeks than to slog your way through Franzen’s overhyped, sloppy, if occasionally entertaining six-hundred-page mess of a novel.

Instead, with The Suburbs, Arcade Fire offers a sixteen-song treatise on the lost promise of the American dream as exemplified in neighborhoods where “First they built the road, then they built the town / That’s why we’re still driving around, and around, and around and around.” That the ensemble does so in moody anthems and upbeat rockers that are pitched perfectly to their subject matter — with music that variously nods to the Kinks, the Who, the Byrds, Pink Floyd, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, R.E.M., Blondie, the Cure, U2, Depeche Mode, the Strokes, and Radiohead, among others — just makes it all the more entertaining, in a manner similar to how the Beatles captured the zeitgeist of 1967 with the landmark concept album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Indeed, Arcade Fire adopts more than a few of that album’s stratagems, including songs that flow into each other and repetitive musical themes, lyrical hooks, and reprises.

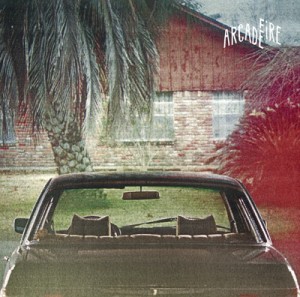

But in spite of its Anglophilic musical tendencies, The Suburbs is a quintessentially American album, one whose closest precedent is Bruce Springsteen’s landmark 1975 breakthrough, Born to Run. Whereas the latter took as its subject matter a somewhat romanticized view of suburban life and car culture, thirty-five years later, Arcade Fire revisits some of the same territory and comes up with a much more ambivalent view of the world of shopping malls and buried highways.

It’s surely no accident that the leader of Arcade Fire, Win Butler, along with his brother and bandmate, Will Butler, grew up in a suburb outside of Houston, that monument to American capitalism and the oil industry that feeds America’s thirst for sprawl and that inspires several of the songs on The Suburbs, including two that use the term “sprawl” for their title.

“In the suburbs I learned to drive, and you told me we’d never survive” are the first words Win Butler sings on the bouncy title track that kicks off the album. That sentence pretty much embodies the dichotomy examined in all its many facets over the course of the next seventy minutes: the sense of youthful nostalgia and promise embedded in the housing developments and freeways versus the painful reality of the boredom and ennui that afflicts so much of suburban life, which, for better or worse, is pretty much synonymous with American life.

In “Modern Man,” Butler encapsulates the quintessential moment of suburban anomie as he waits in line at the supermarket deli counter for his number to be called. In this song, the narrator is seemingly OK with this fate: “So I wait my turn, I’m a modern man / And the people behind me, they can’t understand.” It’s an early hint that Arcade Fire is not out to condemn wholly the promise of the suburbs, but rather, to come to terms with its successes and failures.

On the first half of the album, the songs seem to come down on the side of those who still find much to approve about suburban life. The Springsteen-like anthem, “City with No Children,” paints a bleak portrait of urban life as sterile and infertile, “a garden left for ruin by a millionaire inside of a private prison.” And “Rococo” sides with “town” in a kind of town-gown battle waged against “the modern kids” who “build it up just to burn it back down” while “using great big words that they don’t understand.”

But as one might expect, things turn about halfway through, when, in “Suburban War,” one of several songs that begin by taking a drive, the narrator is unsettled by the sight of the neighborhood in which he grew up, where “they keep erasing all the streets” and “all [his] old friends are staring through [him] now.”

This isn’t to give the impression that The Suburbs main achievement is dialectical. Rather, it’s the wide-ranging musical palette, the reach of symphonic rock awash in synthesizers rubbing up against the electro-punk of “Month of May” (think Bowie in Berlin), and the not-inconsiderable sense of humor and self-deprecation occasionally on display (“Put the laptop down for awhile,” “Now they’re screaming, ‘Sing the chorus again!’” and “Oh my dear god / What is that horrible song they’re singing?” are just a few jokes embedded in the lyrics) that make The Suburbs a vivid, sonic pleasure. It’s an emotional album, or rather, a collection of songs of wildly conflicting and conflicted emotions, reflected in Butler’s harried, David Byrne-like tenor and in Régine Chassagne’s (aka Mrs. Win Butler) detached, icy, Debbie Harry-like Europop responses.

On another level, The Suburbs is a cycle of love songs about an ambivalent relationship; in this case, the lover is home, where home is a place about which you feel ambivalent — an unreal place, built on a house of cards, the false promise of the American dream — the suburbs.

In the end, though, The Suburbs is a sprawling, epic rock album, like Pink Floyd’s The Wall, that encapsulates and speaks to the condition of a vast army of potential listeners and fans. Arcade Fire is aware of its reach, and of the Pink Floyd connection, as they paraphrase one of that legendary band’s album titles, Wish You Were Here, which, like The Suburbs, was also a song on the album: “Wishing you were anywhere but here/ You watch the life you’re living disappear / And now I see we’re still kids in buses, longing to be free.”

It’s a sentiment and theme that is familiar to those who’ve read Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, but rendered much more artfully and with greater care, craft, aesthetic beauty, and entertainment value. If Franzen’s book, as has been suggested, is the “Great American Novel,” at least of our time, then The Suburbs is the “Great American Album.” And it’s also proof that the album — like the novel — is not dead.

==========

This column first appeared in the November-December 2010 issue of Berkshire Living Magazine, as part of the “Beat Goes On” series of columns for which editor-in-chief and music critic Seth Rogovoy was annually honored with an award for General Criticism by the National City and Regional Magazine Association.