There is an emerging consensus that life after the COVID-19 pandemic – if there ever will be such a thing – will not look exactly like life before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nor should it. And I’m not only referring to changes that will be made in direct response to the spreading of disease, or an enhanced awareness of viral and bacterial transmission and efforts that can, and will, be taken to minimize the spread of disease.

Measures like these will of course become routine – subway trains will be cleaned more often; touchless payment systems will pop up everywhere; plexiglass sneeze guards will remain in place at store checkout lines and pharmacy counters. Maybe even that most disgusting and pointless of social habits, shaking hands upon greeting someone, will remain left behind in the ashbin of pre-COVID history, where it belongs.

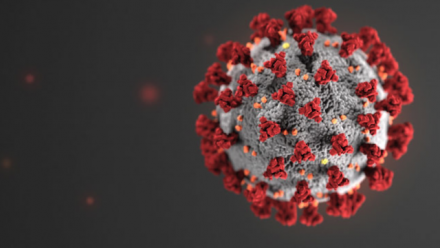

But the unprecedented and sudden threat that the coronavirus represents to our 21st century way of life will result in a lot more than an overuse of ubiquitous hand sanitizers and disinfectants.

The one thing that the shutdown of public life has brought to most if not all has been more time to think, to reflect upon how we have lived our lives and how best to live going forward. The basic human needs still and always will have to be met, what Maslow calls the physiological needs, including food, housing, clothing, and sleep. These needs will never change, but the means through which these needs are met may shift given our new perspective. And surely the ways we meet the other needs in Maslow’s hierarchy, including safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization, deserve a close re-examination.

This is to say that everything and anything is up for grabs. Employers that have successfully shifted the lion’s share of their employees to working from home and in virtual meetings will explore ways to continue these kinds of arrangements, if only for reasons of enhanced productivity, efficiency, and the bottom line. Businesses that lease expensive office space might suddenly discover that they can do without half or more of that square footage, thus shrinking their physical footprint and immediately accruing the reduction in expenses needed precisely at this time of economic devastation.

And workers alike may welcome such changes. Who wouldn’t be in favor of new policies put in place that would reduce or eliminate lengthy and expensive commutes to work, saving them both time and money for other pursuits. Blue-collar workers who by the nature of their jobs have to be onsite in factories or construction sites will return with a newfound sense of empowerment, enabling them to demand better safety conditions and other protections, financial and otherwise, after the crisis has illuminated the unfair labor practices of certain online retailers and dangerous working conditions in factories of mass animal slaughter.

And so-called frontline workers – who in reality are the low-paid service workers who keep everything functioning, whose lives were put at risk by suddenly declaring them “essential” with a stroke of a pen, in spite of them having been treated as anything but essential – will hopefully emerge having gained the newfound respect, and consequently more dollars in their pockets, that should follow in the wake of their role in the economy being recognized as one of much greater social value than before.

But what will be potentially a lot more interesting than all the technical improvements and adjustments over a broad spectrum of the social economy are the changes in perspective that individuals will bring to their own lives and those of their friends and loved ones. Those who will have survived this calamity, this very existential threat, will have shared in a kind of global trauma like no other in our lifetimes. People will emerge with new plans and priorities for their own lives, along with the fears and anxieties that have poisoned everyone, regardless of medical status. Humanity will to a significant extent be a new breed now that our very survival has been challenged.

We will be vulnerable for a time – still vulnerable to COVID-19, to other pandemics, and of course to the climate crisis of which this crisis is just one small manifestation. But we will also be vulnerable to those who see this crisis as an opportunity to amass power out of chaos and vulnerable to the millions or billions who will seek to escape from the chaos of freedom and to trade that chaos for the illusion of control.

It is our job to weigh every choice we make starting now very carefully, to take whatever insights we have gleaned about the way we live and to be mindful of them moving forward, and to recommit ourselves to the challenge of repairing what is broken and to tending our precious garden.